In the brightly lit shop window of La Placette, Grégory Sugnaux offers a virtuously textured surface of painted red and white hues. If we pause to take a closer look at the display, we can see that it is a piece of meat crisscrossed with fine veins of fat. Famous for its tender texture and delicate marbling, this is not just any piece of meat: at a price per kilo of around CHF 450, Wagyū cattle provide the most expensive beef in the world. Given this background, we might be prompted to reflect on the trade of art, the attractiveness of painting on the market, and the sometimes-exorbitant prices paid for individual artworks. If we concentrate on the materiality and the beguiling surface, however, on closer inspection its texture turns out to be a mere illusion. The impression of plasticity is owed entirely to the way the artist juxtaposes different colors. A game of confusion that thrives on irritation and provoked pauses is at the heart of Sugnaux’s painterly practice.

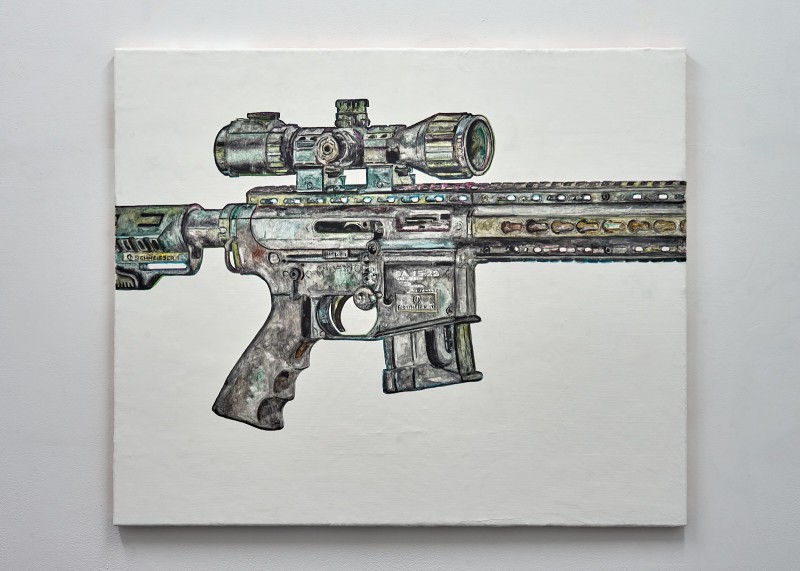

Grégory Sugnaux’s focus lies on the different temporalities of images that collectively form the visual repertoire of our present. The starting point for his paintings is constituted by the stream of snapshots floating around the internet, (pirated) copies, stock photos and memes, some of which have developed a life of their own. What they all have in common is what the artist Hito Steyerl described in 2009 with regard to so-called poor images: they are dematerialized, open to change and modification, and circulate at an enormous speed. Grégory Sugnaux uses software to compile these pictures into a database of ordinary, arbitrary images, which he searches through keywords to find the next subject for his works. Sugnaux’s practice slows the pace of these images: he projects them onto the canvas and repaints the motif in rapid strokes with gouache within a day. Any distortions and refractions of light are transferred to the canvas. The colors only begin to mix there, so that a moment of “independence” or “idiosyncrasy” determines the renewed materialization of the images. It is not a matter of old-masterly perfection, instead the pictures (in their incomplete state) are meant to adhere to the canvas. They remain attached to the multiple layers of white acrylic paint with which Sugnaux primes his canvases. The thick base acts like a skin, provides a viscous texture and plays with the common topos of painting as a (physical) counterpart. A border is marked that seems to suggest an interior and an exterior. But the perception is deceiving — the works do not disclose any profound depths, nor do they proclaim the painting’s sovereignty among today’s images. If the white surface layer develops a tactile sense of seduction due to its seemingly peculiar texture, this is a means to an end to create moments of decelerated reception. Our gaze lingers on this layer of paint, like to the motifs found on it. Consequently, the supposed texture and depth, which, from a distance, seem to be the work of a virtuoso pastose application of paint, become disenchanted. The pictures are flat, their three-dimensionality is an optical illusion resulting from the interplay of the white primer and the densely placed colors.

This conundrum continues on the level of Sugnaux’s subjects. His motifs play with a moment of recognition. It appears as if we may have seen this or a very similar image countless times before. The ubiquity of his pictorial templates has led to a situation where these images are hardly ever looked at closely, but are simply registered in their fleeting appearance. They pass in front of our eyes without being given any particular attention. If we suddenly see them on a canvas in the context of an exhibition, it is impossible to say whether we really already know them. Sugnaux’s art is strangely familiar to us and yet not at all. With his paintings, the artist thus joins the multitude of image-making processes of our present time. They are characterized by a sense of deceleration and obvious materiality that becomes particularly apparent through the contrast of the chosen motifs, their “placeless” sources and their dematerialized circulation. At the same time, this correlation creates the very moment of irritation and rupture, which challenges our common habits of seeing and thus offer a possibility for pause and respite: the motifs are irritating because, due to their omnipresence, we are used to overlooking them. They are not meant to be contemplated, but flicker at the edge of our attention span. They are the visual equivalent of elevator music rather than an image in the privileged sense. The artist thus understands their painterly sedimentation simply as another stage “in the life” of these pictures. They are by no means preserved in an unchangeable form for posterity. Instead, there is a temporary disruption of the image’s circulation, an aesthetic moment of irritation, when the pictures suddenly populate the exhibition space on a canvas instead of on a screen. Likewise, Sugnaux always conceives these works as a group, and rearranges them depending on the exhibition context. This way, he translates the inherent impermanence of his subjects, their susceptibility to modification, to the practice of exhibiting and continuously finds new forms of presentation. The work, despite its painterly nature, is far from being self-contained, but circulates again and again in the context of other paintings. It is an examination of the visual worlds we consume on a daily basis, as well as our habits of seeing, which result from the fluctuation between the digital and the analog. In the midst of today’s flood of images that we encounter with increasing indifference, Grégory Sugnaux juxtaposes his paintings with a perceptual experience that is borne by the question of what contemporary images are and how we approach them.

Texte : Elsa Himmer

Photographies : Nikolaj Tur